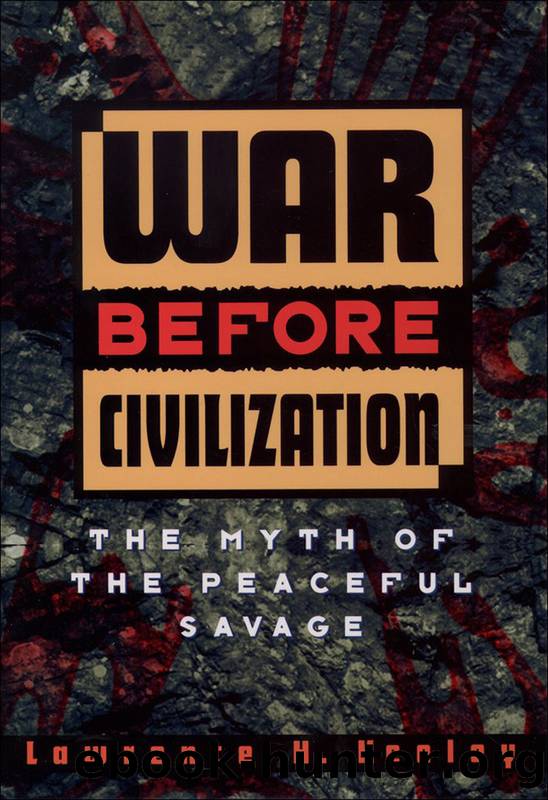

War before Civilization by Keeley Lawrence H.;

Author:Keeley, Lawrence H.;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA

Published: 1996-09-14T16:00:00+00:00

Figure 7.1 Relative territorial gains and losses per generation for various soceities (see Appendix, Table 7.1).

Given the aversion of modern archaeology to the idea of migration and colonization (let alone conquest), the problem of documenting such processes in prehistory is difficult. One archaeologist who has given considerable thought to this problem, Slavomil Vend, admits that annihilation or forced migration would be manifested in the archaeological record only by the âpeaceful existence of winners on the territory of the losers.â33 He gives as an example the victory of the Germanic Marcomanni over the Celtic Boii (from whom the region became known as Bohemia), recorded by Roman historians. Archaeologically, this event is evidenced only by the expansion of Germanic settlements and cemeteries into regions previously inhabited by Celts. An additional difficulty, as we have seen in the ethnographic cases, is that many violent territorial exchanges involve social units that are nearly identical in culture and physique. Prehistory is replete with examples of very distinctive cultures (sometimes associated with distinct human physical types) expanding at the expense of others, but determining whether these expansions were accomplished violently or peacefully is usually no simple task. Several regions of the world offer evidence that at least some prehistoric colonizations or abandonments of regions were accompanied by considerable violence.34 These most visible prehistoric cultural expansions, which involve the movement of a frontier, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

As we have seen, even in situations where no territory exchanges hands, active hostilities along a border can lead to development of a no-manâs-land, as settlements nearest an enemy move or disperse to escape the effects of persistent raiding. Such buffer zones have been reported from Africa, North America, South America, and Oceania.35 As in the Wappo-Pomo case, encroachment on these zones by the stronger, more land-hungry, or more aggressive adversary was a common mechanism by which tribal warfare led to the exhange of territory, even in the absence of any clear design. The width of these no-manâs-lands varied with population density.36 High-density economies could afford to concede only a small amount of land to such low-intensity use and had a limited capacity to settle elsewhere refugees who fled such zones. Moreover, the higher the settlement density, the more eyes there were to watch for raids, the more rapid the communication of alarms became, and the more quickly local forces and allies could respond to incursions. Thus no-manâs-lands tended to shrink with increasing human density because they became more costly economically to create and because the security belt they provided was less necessary.

Where population density was high, these buffer zones were measured in hundreds of meters, as in highland New Guinea. Where density was lower, their width stretched to tens of kilometers, as in the more lightly populated areas of the Americas or in the dry savannas of Africa. Although such buffer zones could function ecologically as game and timber preserves, they were risky to use even for hunting and woodcutting because small isolated parties or individuals could easily be ambushed in them.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41524)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(32882)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32569)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(17927)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7690)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7135)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6587)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6432)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6270)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6219)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6027)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5820)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(5641)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5384)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5181)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5151)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(4974)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(4837)

Electronic Devices & Circuits by Jacob Millman & Christos C. Halkias(4739)